Hours of the Day

Talk by Ingrid de Kok at Gwen van Emden’s exhibition at the Irma Stern

Museum, Rondebosch on Sat 21 March 11am

Welcome everyone to this special exhibition, Hours of the Day, which takes

place, fortuitously I think, on Human Rights Day. Perhaps before we look at and

think about Gwen’s work, this is a moment to reflect that, in addition to the

crucial rights normally understood as our human rights, all who live in South

Africa should also have the right to encounter, learn about, respond to, and

produce, creative work of complexity and beauty. For this is what we are

privileged to experience today in Gwen’s work, we lucky ones who have so

many opportunities to appreciate the hours of our days, though we seldom use

these opportunities to the optimum.

I am not an artist, but a poet, so I will approach Gwen’s work from my own

personal and creative perspective and without the disciplinary language you

are probably accustomed to at such events.

I am not going to draw your attention to the details of Gwen’s CV, one that

includes academic distinction, solo exhibitions of MFA work, commissioned

curated exhibitions of various collections in collaborations with Rayda Becker,

Pippa Skotnes, Fritha Langerman and John Parkington among others, and

recently a whole slew of group shows. For the past few years she has attended

Rose Shakinovsky and Claire Gavronsky’s renowned workshops at

Goedgedacht and their residencies in Italy, generating a consistent body of

work, shaped and disciplined by her participation in these demanding learning

environments.

I myself have experienced two small collaborations with Gwen, though I

hesitate to call them by such a grand name. When she was curating, with Pippa

Skotnes, the “Curiosity” exhibition for UCT’s Michaelis 175th anniversary, she

and Pippa commissioned me to write some poems about the exhibits, and I

had the arcane pleasure of being led by Gwen on a tour through the objects on

display. I was impressed by the range of her scientific knowledge, her

understanding of machines and processes, of academics and their research

techniques and obsessions. But what was particularly engaging was her delight

in handling small objects, simple or complex: field guides, dassies’ tiny teeth,

titanium implants. Her lively accounts of each object’s provenance and

singularity were striking. She could look at an object as something standing

alone, with its own unique shape and internal history, and she could place it

inside a context, or at an angle to a context, with humour and precision. She

seemed to me to be an explorer of “our laboratory of meaning”, that “archive

of half known things” which I called our system of fugitive signs and discoveries

in the poem I eventually wrote about the collection.

When we worked together again, in 2010, on a LED sculpture” Bits, Bites and

Tweets”, that she made for UCT Summer School, I was struck anew by how

she adapted her considerable research, artistic and technical, almost

spontaneously, to playful purpose.

I think this exhibition reveals Gwen’s special combination of playfulness and

resolve, of chance encounter and attentiveness. Spontaneity and attentiveness

are not in any case necessarily opposed conditions though they live together in

asymmetrical ways. Gwen’s attention, focussed as it is on the everyday, its

absurdities, its unexpected connections, its presences and absences, is a work

in process and that always invites unruly guests, immediacy and the

unexpected. And the quotidian, we all know, appears to us as simultaneously

immanent and ephemeral so it invites respect and wonder as well as levity.

But there is something new too, in the recent work, surely gained from the

Rose and Claire workshops: pleasure and humility in the face of the tradition of

work that has preceded her. There seems to me an increase in focus, without a

loss of playfulness, as she translates into personal language, the contemporary

art tradition of the every day, and takes on new stylistic risks and sorties.

Titles assist us in navigating an artist’s meaning, the moment before we in

effect place our own title upon the works, entitle ourselves in relation to them.

The title of this show matters. Gwen composes inside what I have called in a

poem of my own, about Venice, “the subdivisions of the hour,” itself a

reference to canonical time. The fragments of the day can be curious, banal,

torpid, precious, illuminating, or elusive. The day and its inhabitants, human

and not human, begin, mutate, and end. And the “end” of the day is both the

day’s purpose and conclusion To fully appreciate the hours of the day is the

aspiration, the inspiration of many poets, especially those classically trained

poets of the 17th century, where the admonition by earlier Latin poets to ‘carpe

diem’, Seize the day, became a metaphor for a full encounter with love, desire

and beauty, before inevitable death puts an end to temporary visual or

linguistic pleasures and expressions.

The forty works, called Looking for Art that extend across the wall in the first

room, seem to me to best exemplify the meaning of Gwen’s exhibition title:

“Hours of the Day.” Each is a screenshot taken a few times a day on her phone

as she approached a designated spot at Goedgedacht, and she formulates the

practice as ‘a daily walk in search or art’. Intent on catching each moment,

each experience, to see what happens as it is happening, she photographs her

shoes, the soil, the changing light, the mystery of the approach to an

unrealizable destination. Because of course, there is nothing to be found

except the walking, the searching, the process itself. Nothing is happening,

everything is happening. So she remakes her walk as an artistic object, first on

her phone, then on her computer, then, here, on paper. Below each

screenshot, and using the same grid form, she places frozen images seen on

the slides shown by Rose and Claire as part of the workshop lectures, or

images downloaded from the internet. Those images are juxtaposed as little

guides, units of artistic measurement against which the individual day’s

journey into art, the daily preoccupation with one defined space and its

motility and silence can be assessed or extended. See which little images you

recognize: see Yoko Ono’s fly, the dog in the corner of the Night Watch, Mona

Lisa in her impenetrable glass cage. These works are walking meditations,

working meditations, mediated by contemporary techniques.

Gwen’s quest is to ‘catch the in-between’, and in many of the other works she

is interested in the thin membrane that connects one thing to another, one

person to another, one time to another, one thought to another. Often those

connections involve personal material transmuted by or seen through the lens

of art history. To catch the in-between, to live and make art in the elusive

immediate, is to disrupt the predictable and acknowledge that the everyday,

the quotidian, is composed of ambiguity, persistence and transience, stability

and instability. And there is a long art tradition- in the visual arts, in dance, and

in literature, on her side, by her side.

The And Here sequence of pencil and tape on paper, and the Falling Square

works, all influenced by Joseph Beuys’s work, also have a direct personal

resonance. The falling squares are composed on paper used by Gwen’s father,

a town planner, photographer and mapmaker. As a young girl she assisted him

in his mapmaking room, watching and learning the use of letraset and learning

how to fold maps exactly. What a strange and lovely image for a relation with a

father, and one which results most mysteriously in the 2 elegiac Falling Square

oil paintings. See how marks are caught in the folds of paper, what those

marks tell us and what they do not, and what in-between might mean. In

Natura Morta Morandi, too, she revisits her father’s materials, using grid

paper from his stamp collection.

Further instances of the personal infusing the process of art making are the 3

airy, dramatic paintings above the stairs, Dahlia 1, 2 and 3, the nutcracker

works and others. Pippa Skotnes, after packing up the studio of her father, the

late Cecil Skotnes, gave Gwen pigment which he had labelled “Dahlia” in his

own hand writing. Gwen told me that her mother used to grow dahlias, selling

them to the flower sellers at Church Square. Gwen then used the pigment in

various ways, bringing in effect the domestic- the personal memory of her

mother -into relation with art- the pigment of an artist who was the father of a

friend- strange and unexpected correspondences.

The Hours of the Day, as many of you will know, is a phrase with antecedents

in other worlds, other works, not to mention in our everyday speech. Agnes

Martin in an interview “What is your favourite time of the day?” answered

implacably: “When you leave” and this is referenced ambiguously by Gwen in

a crayon piece on her father’s grid paper. Virginia Woolf famously in her book

Room of One’s Own, which Gwen tells me influenced her a great deal,

implicitly reminds of us how a room divides into hours, and is a reservoir and

delineator of time as well as space. Louise Bourgeois produced works

generated by insomnia, one book of which I think was called “The Hours of the

Day.” And Gwen has always been interested in the exquisite illuminated Book

of Hours manuscripts which provided a visual aide memoire, to women in the

Middle Ages and beyond, recording weekly cycles of prayer and domestic

practices.

To conclude with a final comment and a poem.

I could have commented on many other of the works- the sinister Tooth

Faeries, the elusive fish, my favourite, Lamb, the monotype prints in the pink

room below that are and are not plants. And these boxes in front of me, the

Time Trees, their shadowy innards the painted shadows of a tree at different

times and on different days. They show how one longs to but cannot stabilize,

cannot fix into a template, the hours of the day or daily experience as a whole.

And the Residue works, the results of ‘fluke’ brushstrokes on beautiful

Japanese paper. Rose, talking more generally of this sort of unmediated

process, described it as “Amazing, all those little things that make something

either this or that” and Gwen redefined this to me as “how little you need to

put on paper”. Except of course that what you, Gwen, have put on paper is

little but also not little- concepts and images that can levitate us as well as

settle on and in us. So we thank you for your work and its residue in us.

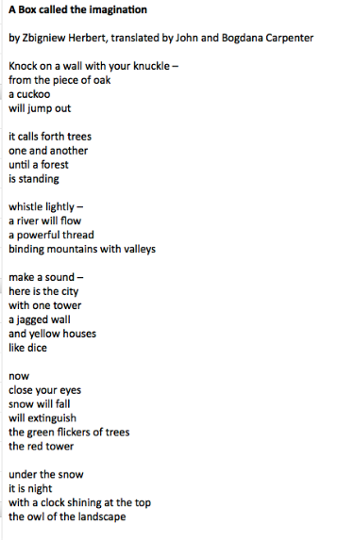

I will finish with a poem by the great Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert. It is his

instructive, luminous poem about the relationship of the quotidian to the

creative mind. It is called “A Box Called the Imagination.”

Please not that this talk is not to be reproduced without the permission of the

speaker, Ingrid de Kok.